Disclaimer: this is a translation of the article written 2 years ago for a corporate blog. Bear in mind, at the moment of the writing I was testing SOAP services and Excel-based import/export at big government project, so most of the examples relate to that experience.

Usability is one of the most crucial quality attributes of an API. Let’s talk about why, when, and how we can assess this characteristic.

Today (hopefully) no one doubts the necessity of usability testing of GUI. Yet, according to ISO 9241, usability is the effectiveness, efficiency and satisfaction with which specified users achieve specified goals in particular environments. There is no mention of menus, fonts, or buttons color. Hence, we can evaluate usability of any product, be it a mobile app, a vacuum cleaner, or an API.

For testing API usability we can use methods developed in the field of HCI; same as used for GUI. Generally, these methods can be divided into two categories: analytical and empirical.

Analytical methods

Analytical methods involve exploration based on some expert knowledge. Loosely speaking, you and/or the whole dev team try to evaluate and find hypothetical usability problems without users input.

Heuristic evaluation

Easiest way is to use heuristics. There are no strict lists of what criteria you should check; all depends on what kind of API you have (e.g., library or REST service).

For instance, a paper on a structural analysis of usability problem categories mentions this set of heuristics:

- Complexity. An API should not be too complex. Complexity and flexibility should be balanced. Use abstraction.

- Naming. Names should be self-documenting and used consistently.

- Caller’s perspective. Make the code readable, e.g.

makeTV(Color)is better thanmakeTV(true). - Documentation. Provide documentation and examples.

- Consistency and conventions. Design consistent APIs (order of parameters, call semantics) and obey conventions (get/set methods).

- Conceptual correctness. Help programmers to use an API properly by using correct elements.

- Method parameters and return type. Do not use many parameters. Return values should indicate a result of the method. Use exceptions when exceptional processing is demanded.

- Parametrized constructor. Always provide default constructor and setters rather than a constructor with multiple parameters.

- Factory pattern. Use factory pattern only when inevitable.

- Data types. Choose correct data types. Do not force users to use casting. Avoid using strings if better type exists.

- Concurrency. Anticipate concurrent access in mind.

- Error handling and exceptions. Define class members as public only when necessary. Exceptions should be handled near from where it occurred. Error message should convey sufficient information.

- Leftovers for client code. Make the user type as few code as possible.

- Multiple ways to do one. Do not provide multiple ways to achieve one thing.

- Long chain of references. Do not use long complex inheritance hierarchies.

- Implementation vs. interface. Interface dependencies should be preferred as they are more flexible.

Let’s try to apply some of these heuristics.

There was a time when every new tester came to me during the onboarding and asked about the error message “House with ID <> was not found.” I told them to use internal system id instead of global FIAS id (Russian index system for buildings). And every one looked startled and answered me that there is no such parameter in the API request! Well, the problem was that you had to use the same parameter named FIASHouseGUID. For some reason when system was designed no one thought that the better name would have been HouseID as it could be filled either with FIAS id or with internal id. Even though current name was misleading (naming heuristic), it was no longer possible to change without breaking backward compatibility.

Next example is about error handling. One service I tested had a very common error “Access is denied.” There were numerous reasons for this error: no entitling documents, documents are not in the status “published,” other organization already created the same object. Reasons were different, but the received error message was the same; users couldn’t guess what was their problem.

There are other, more “serious” heuristics for API. Often they target specific technical details. You need to be able to code to understand them. For example, criteria from Joshua Bloch. Or a usability research made by Microsoft to determine which constructor is better: default constructor with setters and getters or constructor with required parameters. Results showed that the first method was more preferable; this became a heuristic for library design.

Cognitive dimensions

These are distinct criteria used predominately for evaluating usability of notations, user interfaces, and programming languages — or, generally speaking, information artifacts. In my view, they intersect with some heuristics, but there is a difference: heuristics are contextually selected by some experts, whereas cognitive dimensions are more or less stable set of principles. You can read about the main set described by Thomas R.G. Green and Marian Petre in the Wikipedia.

Some companies customize cognitive dimensions for their needs, like a framework suggested by Visual Studio usability group:

- Abstraction level. The minimum and maximum levels of abstraction exposed by the API, and the minimum and maximum levels usable by a targeted developer.

- Learning style. The learning requirements posed by the API and the learning styles available to a targeted developer.

- Working framework. The size of the conceptual chunk (developer working set) needed to work effectively.

- Work-step unit. How much of a programming task must/can be completed in a single step.

- Progressive evaluation. To what extent partially completed code can be executed to obtain feedback on code behavior.

- Premature commitment. The number of decisions that developers have to make when writing code for a given scenario and the consequences of those decisions.

- Penetrability. How the API facilitates exploration, analysis, and understanding of its components, and how targeted developers go about retrieving what is needed.

- API elaboration. The extent to which the API must be adapted to meet the needs of targeted developers.

- API viscosity. The barriers to change inherent in the API and how much effort a targeted developer needs to expend to make a change.

- Consistency. How much of the rest of an API can be inferred once part of it is learned.

- Role expressiveness. How apparent the relationship is between each component exposed by an API and the program as a whole.

- Domain correspondence. How clearly the API components map to the domain and any special tricks that the developer needs to be aware of to accomplish some functionality.

Here is an example for domain correspondence. Service main entity was a house. Common apartment building can have several entryways, each leading to set of apartments. But in Kaliningrad this doesn’t apply: a typical address there can look like “2-4 Green Street,” where entryways are house 2 and house 4. This bizarre (and initially unknown) domain model broke the whole logic behind API design. For instance, we had to allow users to add house-level metering devices to entryways if it’s actually a house.

Cognitive walkthrough

While the first two methods are based on checking API against some kind of list of criteria, cognitive walkthrough is closer to scenario-based testing. Essentially, an expert comes up with typical API usage scenarios and attempts to perform them.

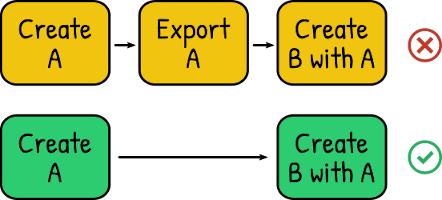

You can combine this method with heuristics. When we analyzed services, we found out that there were problems with the consistency: when you sent a request to create an entity, some services responded with entity version id, while others provided root id. Moreover, most of the services required entity id for creation of other entities, and again, it could be either root or version id. It didn’t look that bad, until we tried walking through a business scenario:

- Create an entitling document

- Create a metering device providing document root id

In existing API workflow you had to do it in 3 steps instead of 2:

- Create an entitling document → server responds with document version id

- Retrieve the document using provided version id and get document root id from the response

- Create a metering device providing document root id

This middle step is objectively unnecessary and generates additional server load. Here, using cognitive walkthrough, we also detected an inconsistency with heuristic “minimal working code size.”

API peer review

Heuristics and walkthroughs are great methods, but they could be quite subjective. For better objectivity you’d better use group evaluations, where several persons analyze API. You can read about how and why this method can find usability problems which are rarely found by empirical methods in this Microsoft paper.

Peer reviews involve these four roles:

- Usability expert who will organize and moderate the evaluation process from usability perspective

- A person who is an owner for the specific API chunk under review

- A person who is an owner of the API unit (or system) where the reviewed chunk resides and who knows the context of API usage and its interactions with other APIs

- 3-4 persons who will complete some task which will be used to actually evaluate usability (usually just other developers)

During the planning process, a usability expert and a chunk owner should discuss:

- Key tasks to be completed during the review (e.g., how to create a document using an API)

- Code examples to be reviewed

- Who are the other participants (they can be selected based on specific criteria, like knowledge of SOAP services and Java)

- Place and time for review session

You should start a peer review session with the explanation of how this meeting will proceed and communicate basic information related to the evaluated API chunk. Next you distribute code examples and discuss them, asking these main questions:

- Do you understand what this code does and what its objective is?

- Is this objective achieved in logical and rational manner?

Based on the answers, a usability expert asks to elaborate details. For example, hearing that naming is weird, expert should ask why a person thinks that way and what different name would be better.

The final step is to analyze problems. Here is where an API unit owner can help to identify the most significant issues and could they be resolved or not.

That’s the end of part one. Empirical methods are covered in part two.